After the Fire: The Collateral Damage of Vancouver's Housing Crisis

It was August 26th, I was browsing the internet during slack time at work. "WTF is on fire downtown??" asked someone in the /r/Vancouver subreddit, posting a picture of black smoke billowing from somewhere near the edge of Strathcona. It soon became clear that a home was on fire in that neighbourhood. As I glanced at my Facebook feed through the rest of the day, something else became clear: that I knew a person who lived in that home.

More accurately, it was my partner's friend Erin. I'd never met Erin in person, but she was one of those people who, as happens in our modern lives, I knew obliquely. My girlfriend hung out with her now and then, and I'd interact with her in the comment threads of other people's Facebook posts. After hearing that she was okay, my next thought was a blend of panic and concern: Where is she going to live now?

In the summer of 2016, Vancouver's rental vacancy rate dropped to 0.6% . With such a highly competitive market, landlords can charge premium rent for lackluster suites. What's more, landlords often require their applicants submit extremely personal information and undergo credit and background checks. No smoking? No pets? Try no cooking, no guests... perhaps they'll even expect the occasional massage or booty call. The Vancouver landlord demands an obedient, bespoke tenant. Furthermore, landlords know that although some of the aforementioned demands aren't legal, no applicant will complain, because the applicants desperately need housing. So, finding a house, even under ideal circumstances, is a daunting, near-impossible task.

Obviously, Erin's circumstances were not going to be ideal.

Erin grew up in Kelowna, and moved to Vancouver as a young adult, in 2008. She works two part time jobs, and was planning on attending UBC this past fall for philosophy, since she has a keen interest in the field of bioethics. I talked to Erin about her experience the day of the fire:

"I was at home alone, it was around noon, and I was just getting ready to go out. Suddenly, one of my neighbours around came banging on the door, yelling, 'Fire! Fire! We have to get out!'"

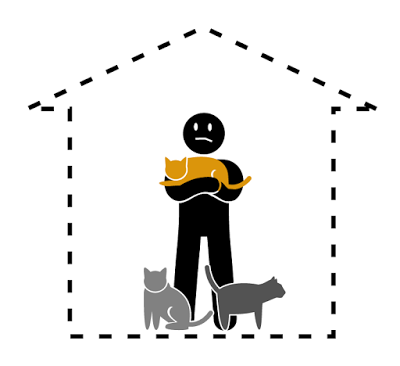

When Erin looked outside, she could see that flames were pouring out of the window of the neighbouring suite. In a panic, she tried to herd her three cats into their carriers, but it became clear that there wasn't time, and she was in danger. Discouraged, she was forced to flee her suite.

"The fire department arrived quickly, but it was an hour and a half before firefighters were able to go in and get my cats out."

The building was an older, renovated, six-unit apartment building. "We found out later that the neighbours in the unit where the fire started had left their stove on – a gas range."

After the fire was out, Erin and her roommate were allowed to go into their suite to get a change of clothes and toiletries, but only because their suite was relatively removed from the fire damage. Vancouver Social Services arrived and gave everyone a food voucher. They also put everyone up in a hotel for the next few days, but every one of the tenants had pets, for which the tenants needed to find additional accommodations. After another few days, some of the tenants were allowed to go in again for a quick move-out. With some effort, Erin managed to rent a van and a storage locker on very short notice.

"I was able to stay at a friend’s at Knight and 59th, which is pretty far away. I don't have access to a vehicle, so I'd have to leave significantly earlier just to get to work on time."

Not knowing what her circumstances would be, Erin made the difficult choice to withdraw from her coming school semester. "I had no idea how long it would take me to find something. I was seeing ads asking $1,450/month for a bachelor suite. I sent like 20 to 30 e-mails per day sometimes, most of them didn’t even get responses. And each place I went to see, there were at least ten other people looking at the suite. In some cases, all the applicants were there at the same time, filling out applications."

"I only was invited to look at eight places. I made offers on all of them. I saw people begging to the landlords – twice I saw people crying. People had their references on speed-dial. It was very competitive, very strained."

If such circumstances weren't constraining enough, Erin had to grapple with being a pet owner in a city of landlords notorious for not wanting pets. But she wasn't prepared to give up her cats: "I had to watch my building burn knowing my cats were inside. I wasn't going to give them up after that because a landlord wouldn’t let them stay."

Luckily, Erin's story has a happy ending. After furiously hitting the rental listings, she was able to find something for the middle of September. However, her outlook remains pensive.

"All things considered, I was very lucky."

"I have a steady income, I have savings. I got my deposits back and all I lost was a clock that I didn’t like that much anyway. But what if I had a serious disability? What if I was elderly? What if I had no savings? Circumstances in addition being very suddenly displaced from one's home, in this rental market? That could be insurmountable."

Indeed, the price of housing in Vancouver has hidden, yet wide-reaching societal costs. As blogger/journalist Cory Doctorow recently wrote:

Housing ranks just below food on the hierarchy of human needs. Stability in your shelter is the key to stability in every other area of your life. Precarious housing undermines family life, education, and work performance. ... Treating housing as an asset class means that governments want to make it more expensive -- if a government presided over a doubling in the price of food, it would be viewed as monstrous. If it doubles the price of housing, it is lionized for "increasing property values."

Vancouver's housing crisis, fuelled in part by wealthy foreign speculators, means that child poverty is on the rise. It means strained romantic relationships. It means that women aren't able to escape from abusive relationships.

Personally, I know of a couple who have now been rennovicted twice in the space of two years. Another couple, who just had their first child, were evicted and weren't able to find anywhere to live. The new mother is my friend Yaara, who has lived in Vancouver for nine years. She and her newborn have now temporarily moved back to Israel, to live with her parents.

I have lived in Metro Vancouver since I was twelve – that's 25 years. My closest friends are here. My father, my girlfriend's parents', our jobs – all here. I have been told by some that living in Vancouver is no longer realistic for a household of our income range. Though not meant in malice, it's an extremely unhelpful suggestion.

I decided that I'd end my interview with Erin by asking her outright: is it unreasonable for us to expect to live here? Should we just go somewhere else? Pausing, she took a deep breath before answering:

"Well, I have health issues that are exacerbated by cold. I don’t drive, so I need to live somewhere that has accessible public transit. Here in Vancouver, I have two jobs which have good long term prospects. My support network of friends is here."

"But, more to the point, why should anyone be displaced from where they live? Whether you’ve lived here for a few years or your entire life, why should you have to leave in order to accommodate people just because they’re higher on the socio-economic ladder than you are?"

My partner and I are grateful to have a landlady who wants to exchange a reasonable rate of rent for friendly tenants. Many of my peers are not as lucky. I hold out hope that, within my lifetime, our society will internalize the idea that the basic essentials of living are not products, or investments to game against the market.

Food is for eating. Water is for drinking. Homes are for living.

Cover image: "3 Cats, No Home" by Jesse Schooff

created using vector art by Leremy/Shutterstock